COVID-19's disruptions to daily life are nothing new to the students of the Exceptional Academy

DETROIT - Coronavirus may have shuttered businesses, ended school years and upended our day-to-day lives, but it hasn’t slowed down the students of the Exceptional Academy.

To them, working through daily disruptions is just good job training. Studying to work in the field of cybersecurity, the students enrolled in the program will soon be entering a field that demands an adaptive work style.

“That’s a part of the industry they’re getting into. A lot is done remotely through all these applications,” said Anita Sefton, who manages the program. “We have had no change in our timeline, we’re just coming at it a different way.”

Classroom lectures are now done in online video conferences. Lab work has been converted into daily assignments due the next day.

Daily disruptions aren’t just a part of the careers these students hope to enter, they’ve been an innate part of life too.

Before Ian Cashero applied for the program, he was working as a janitor for the city of Livonia. The job was easy enough and helped him out of a downtime in his life. While no stranger to odd jobs as a security guard or dishwasher, the 25-year-old had come out of high school with aspirations of working as an electrical engineer.

But in August 2019, Michigan Rehabilitation Services (MRS) told him about a program out of the Living and Learning Enrichment Center in metro Detroit. An extended learning course that ran from September to July, the program was designed as a post-high school program that catered to students with special needs.

“When I learned about it, I wanted it instantly,” Cashero said. “I wanted to get a real job and career during a point where I was going through a rough period. I’m forever thankful for the people who gave me the opportunity to do any and all of this.”

Cashero has high functioning autism. He’s well aware of the stigma society has placed on individuals who are differently-abled. He’s also aware that such a stigma means so many others on the spectrum are relegated to jobs that keep them from achieving their full potential.

Which is why the 40-week-class out of the Living and Learning Enrichment Center in Northville is considered innovative and unique. Only the third of its kind in the world, the first specialized Cisco Networking Academies like this started in New York City and Vienna, Austria. The classes are modeled off of a program a former employee at CISCO created to train people with special needs to become CISCO certified network analysts or CCNAs.

"Every company is trying to hire for cybersecurity. They're worried about getting hacked. Unfortunately, there's not enough workers (to hire)," said Pat Romzek, the architect of programs like the Exceptional Academy. "Meanwhile, you have millions of people capable of doing these jobs - they just lack the education and work experience to get them.“

Instead of enrolling students with disabilities through a traditional education and work setting, the Exceptional Academy looks more like a trained-to-hire program which helps certify and prepare the students for a specific job.

As with every “first-time,” administrators anticipated some bumps along the road. The material can be dense, so lectures needed to slow down and cater to each of the 14 student’s learning styles. Some students struggled at first, unsure if they could handle the workload, while others were forced out of their comfort zones when interacting with other students or guest speakers.

Then something happened no one had prepared for: COVID-19. Forcing families to stay home and the public schools to close, the global pandemic has essentially put a hold on formal education until further notice.

But not for these students.

“This is how we operate, this has never been done before,” said David Franco, director of business development at the center.

While the rest of the world’s status quo has been disrupted by the virus, Franco says it’s nothing new to people with special needs. Their lives have always experienced disruption. For the students in the Exceptional Academy, coronavirus is just another hurdle to overcome.

“I think if we were to stop and halt (lectures), I think it would be a hundred times worse,” said Sefton. “They need that structure and they’re going to come out of this so much stronger because you have to learn to adapt. That’s a part of the industry they’re going into.”

Which is why class was moved online even before the Michigan Governor closed public schools in March.

“We’d practiced this before. Working remotely is part of the profession and this was important to practice that. So we had done it a few times,” said Steven Kilduff, a teaching assistant who meets individually with each student. “Anyone reading the news could smell it (school closures) coming. And if they were shutting things down, we had a contingency plan in place.”

Granted, most students already knew the Internet well. Transitioning online wasn’t too tricky - in fact, some students began to engage more after moving to online lectures.

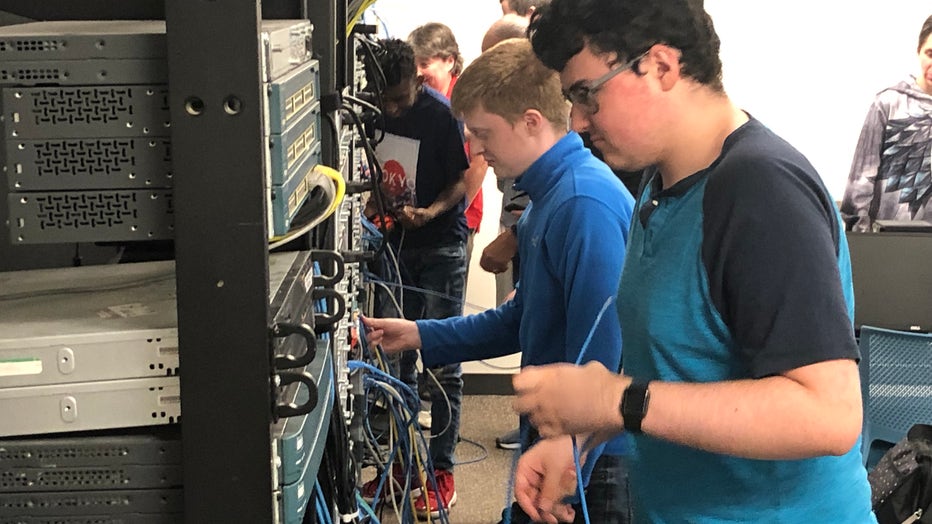

The students of the Exceptional Academy out of Northville. Photo taken earlier this year. (Living and Learning Enrichment Center)

But it also meant no more face-to-face interaction. Job shadows like the one to Plante Moran earlier this year were put on hold. Where students originally met at Madonna University four times a week for lectures and once a week at Washtenaw Community College (WCC) for lab work, now they’re calling in on Microsoft Teams for a video conference for two to three hours a day.

“I cannot tell you how proud I am of these kids,” said Mike Galea, who instructs the course. “To be honest, I’m putting more time than I ever imagined. This is extremely rewarding for me.”

Galea was brought out of retirement to teach the class. Previously, he taught the same certification course at WCC before quitting in 2019. He describes the teaching profession as a frustrating one. Not as many students care to do their homework or fewer are interested in the material. In online settings, it’s even harder to keep individuals engaged.

“You have to have a passion for the field, you got to have the interest and that’s what we have here,” Galea said. “Most of these kids are very smart and some are just freaking brilliant.”

One of those kids is 25-year-old John Ferella who was planning to go to Schoolcraft College at the time he heard about the Exceptional Academy program. Ferella’s only work experience was an employment at Del Taco. However, after growing up with a fascination for the Internet, it was an easy decision.

“I’ve been on the Internet since I was 9 years old and have always had a desire to know how it works,” Ferella said. “I told the teacher at our first progress meeting, ‘I couldn’t tell you what a switch was.’ Now I’m doing pretty well for myself. Some students need extra help, some students need a little more help than others, but it’s a tricky subject.”

CCNAs are tasked with maintaining all the switches, routers and firewalls that “glue the Internet together” as Galea puts it. Having little to do with computers and everything to do with the connections between those computers and their servers, specialists in this field are in demand in the field.

As the lives around consumers become more integrated with technology, from autonomous vehicles to smart fridges and thermostats, there’s a greater need for people who understand how those machines connect to the rest of the world, and how bad actors can exploit them.

“Consumers use a lot of this stuff who won’t be professionals, so you need professional to secure them,” Ferella said. “We don’t have nearly enough.”

Prior to programs like Romzek's being deployed, there were very few avenues available for people with special needs to find full-time jobs in the information technology field. Romzek, whose son has down syndrome, first came up with the idea about four or five years ago after noticing a lack of people with disabilities working in full-time jobs. He developed a program with CISCO called Life Changer that would prioritize hiring students with special needs.

But very quickly he noticed a problem.

"The more people we hired, the harder it was to find them," he said. "Normally when you do something new, the more you do it, the easier it gets. This was the opposite.“

To work in cybersecurity, the industry prefers a college degree and full-time work experience. Unfortunately, the barriers students with disabilities meet on the way to securing both make it almost impossible to complete.

"If you take 50 people with disabilities, only one or two out of 50 will have a four-year degree and full-time work experience," said Romzek.

Romzek's math may not be far off from the real estimate. About 13% of the country has some kind of disability. Of that group, only 62% graduate from high school. From there, about 42% enroll in college and about 16% finish with a 4-year-degree. Of the fraction of individuals that make it that far, a little more than half are hired.

"All these people are left behind. These students in Livonia (the Exceptional Academy) were left behind," Romzek said. "It's like climbing a mountain. There are so many inherent barriers for people with disabilities today. They're often not given the right support even though they're capable of so much more. It's like jumping over a bunch of hurdles - maybe they can jump over one or two, but maybe not 10.“

With financial assistance from MRS and other contributing help from the Michigan Career and Technical Institute, the state has sought to bridge that divide between businesses and students with disabilities. For the companies that sponsor the Living and Learning Enrichment Center and are actively hiring workers with special needs, which include Comerica Bank, Flagstar Bank, Masco, and Plante Moran, they’ll have internship positions open to students that pass their certification test in July.

“They (the companies) are investing in this class and to these students. The more people we get involved, the better we can do at opening eyes and changing perceptions,” Anita Sefton said. “I see it as a community thing. We all still need a village. I don’t care how old you are or where you come from, we all still need a village.”

Jack Nissen is a reporter at FOX 2 Detroit. You can contact him at (248) 552-5269 or at Jack.Nissen@Foxtv.com