'We've arrived,' Experts see climate change's hand prints all over Detroit's summer of severe weather

DETROIT - Since June 1, 2021, Southeast Michigan has seen more than 80 severe weather warnings. Normally, the region gets 97 of those alerts in a single year.

But Metro Detroit's summer has been anything but normal. It came with 13 tornado warnings, 64 severe thunderstorm warnings, and four flash flood warnings. We’ve almost doubled the number of alerts from 2019. In 2018, only 15 alerts were issued the entire year.

What’s going on?

"We’re here. We have arrived," said Pete Larson, a public health professor at the University of Michigan.

Researchers that study disease, urban planning, public health, and severe weather no longer see predictors of climate change on the horizon, but symptoms of warming trends materializing. And when they appear, it’s often with devastating effects.

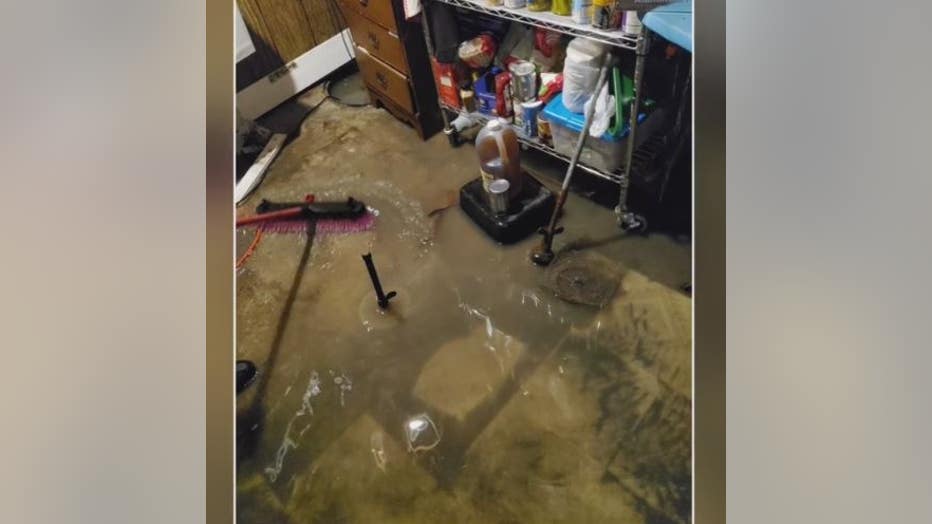

Basements flooding, disaster declarations, and severe weather alerts are no longer reserved for the rare storm event. They’re the consequence of warming patterns that unfurl across the U.S, experts say. Instead of weather conditions trending near the average rainfall or temperatures metrics each year, Metro Detroiters are hit with extremes on both ends.

Only eight years ago, the Great Lakes were at record lows. But last year, the pendulum swung the other direction when they hit record highs - which brought in a large number of flash flood warnings. As scorching temperatures shattered old records in the Northwest this summer, Detroit and Dearborn were submerged in some of the highest totals of rainfall in a single day.

Some look into the past and see shades of 2014 - when a week of rain created a $1.8 billion nightmare in Metro Detroit - the costliest weather event in Michigan history. But experts worry that it's the future that residents and public officials aren’t paying enough attention to.

All that flooding wrecks houses - often homes owned and lived in by people who don’t have the means to pay for damages. But natural disasters also worsen public health issues by making shelters unliveable and mold-infested, which can contribute to higher rates of asthma.

"We’re going to have to find a way to better deal with it - we need to adjust and adapt to all of this," said Jeffrey Andresen, a Michigan State University climatology professor. "The real problem with this is it’s much more difficult to cope or adapt quickly to extreme events than to a gradually warmer and wetter world."

And as the United Nation’s climate report made clear this week, a hotter future is already guaranteed.

Explaining this year’s severe weather bug

Extreme weather doesn’t fit neatly into the climate change models. One happens in an instant. The other is the makeup of decades of data.

Experts like Andresen won’t say climate change caused any single extreme weather event. But the conditions created by warming trends can make it more likely that severe weather will occur.

"As the climate does change - usually it’s a type of gradual change - we increase our chance of probabilities of extreme or short-term storms," he said.

To create rain, a region needs two things: a source of water and a way of lifting up that water. The Great Lakes has a comfortable supply of both. Most of the water vapor that eventually turns into rain in Michigan starts in the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. It can come from other places too - like the surrounding lakes and plants from the heavy density of surrounding agriculture.

Severe Weather Awareness Week: The dangers of flooding

Flooding is dangerous and costs Americans millions.

Then, as the winds circulating around a low-pressure system moves in, they lift that vapor high enough into the atmosphere where it cools, condenses, and falls as water droplets.

That's how you make rain.

But what happens if you ramp up the dosage of one of these ingredients? The Midwest has certainly seen more rain in the past few years. A report from the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments found annual precipitation in the region has increased by 14% since 1951, with the greatest increase happening in the winters and springs.

Meanwhile, the NOAA data from the National Centers for Environmental Information calculate this is the second wettest five-year period in Great Lakes history. June 2021 was the 10th wettest month in Michigan history when an average of 4.9 inches fell on the state. Detroit recorded more than 6 inches in its historic June storm alone.

There’s a growing consensus that higher temperatures are the culprit behind the heavier amount of rain and snow. Warmer conditions can hold more moisture. Most residents may remember the relentless humidity in late June. As more vapor builds up, the chance for a larger storm increases. If the right wind conditions move in - as they did on June 25-26 of 2021 - all that moisture moves with it until it precipitates.

"The warmer air can hold more vapor, so there’s always more potential for extreme events," said Andresen.

Ironically, the gradual intensification of agriculture in the Midwest may also be keeping Michigan from getting too hot. The Great Lakes may not suffer the same scorching heat inflicted on the western U.S. because all of the evaporation that plants are doing is sucking some of the energy out of the local system. If there’s less energy in the system - it can’t heat the surface as much.

Climate models predict that in the next 50 years, it will be two degrees warmer - which will contribute to 20% more precipitation, Andresen says.

How floods worsens poverty

All that water has to go somewhere, and for old cities like Detroit, it’s likely going to end up in the basements of homes every time the infrastructure built to channel it fails.

But where homeowners see another headache when water pours through their windows or sewage bubbles up into their basements, researchers see another part of the public health crisis that afflicts those in poverty.

A survey of 3,842 homes in Detroit found that 2,085 (54.26%) of them had flooded between 2012-2020. The survey also found that rental-occupied homes were more likely to experience flooding than owner-occupied homes, due to poor housing conditions like broken roofs and cracks in basement walls.

Additionally, homes that had conditions associated with flooding like states of disrepair were also found to have higher rates of asthma, which can worsen when mold is present in a home.

Severe flooding in Dearborn Heights leaves residents using kayaks to get around

Some residents took to the streets in kayaks just to get around - and to help others.

Dr. Larson, who led the study that was published in July 2021, argued that it wasn’t just the massive flood events akin to those of last June or the summer of 2014, but the more periodic storms that may not register as massive disasters but still saturate homes in water.

And the poorest neighborhoods often suffer the most from these events - both big and small.

"If you have water come in every time it rains, it leads to mold growth, bacteria, and microbes, which is associated with asthma in adults and children," he said. "With climate change becoming more intense, with poor infrastructure that doesn't divert water, and failing homes, all these things together put people at constant risk."

The poster child for recurrent flooding in Detroit is the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood. One of the city’s older districts, it used to be a swamp before canals were dug through part of the neighborhood giving it a likeness of Venice, Italy. It offered a backyard with river access to its wealthy residents decades ago.

RELATED: Detroit's Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood devastated by flooding again

Many of those original houses are still standing. But they were also built decades ago and weren’t constructed to withstand 21st-century storms. Now a flood-prone neighborhood whose residents periodically throw out damaged possessions from the previous night’s storm, many see more damage to their homes every year.

With enough money, Larson argues, those homes wouldn’t bear witness to the same tragic stories every year. In Grosse Pointe communities, which manage similar severe weather conditions and flooding as Detroit, homes are better prepared to deal with flooding.

Raw sewage flooded basements on Hennepin Street in Garden City.

But those households have more money to spend, Larson says. Many that live in Jefferson Chalmers are elderly residents on disability and lack the financing to upgrade their homes. Instead, the people living there are doomed to live in a cycle of flooding and drying out every year.

If cities can’t find a way to help improve those homes, it might mean harder decisions like telling people where they can and can’t live are on the way. "It requires thinking of who is in harm’s way and how we help them," said Richard Norton of a professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Michigan.

"African American groups live in hazardous locations because that was the last place available. But when we start moving people, that means moving the folks that have always gotten the short end of the stick."

"It needs to be emphasized that homes should be safe places to live in. Right now, people in Detroit are all being impacted by flooding, to some extent or another," Larson said. "These people are not in a safe place to be in and that’s an unacceptable situation to be in."

A Detroit-based solution

Climate change is an urban planning problem too. But that’s where Detroit is different than its Rustbelt cousins in that regional planners see a Motor City-unique solution to its flood problems.

The answer lies in all that vacant land now available.

Larissa Larsen, the chair of Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Michigan Taubman College, believes urban centers will need to upgrade their grey infrastructure - the plumbing that moves excess water through the city. But she also thinks Detroit needs to get creative with green infrastructure to keep afloat.

"Both are needed - we can’t have one or the other," she said. But, "there’s an opportunity for rain gardens and impervious pavement that people are exploring that in different parts of the city."

Plots of land like rain gardens and gullies act like sponges, soaking up much of the water that flows toward it. Firms like Friends of the Rouge and Detroit Future City offer grants and help design and build throughout the city.

The burden will also fall on cities to build more robust green infrastructure, like expanding riverfronts into parks that can flood without damaging neighborhoods. Enough of a buffer would protect businesses and homes.

RELATED: How Detroit's vacant land problem became a solution

But right now, we’re dying by a thousand cuts, Norton says. "Storms will get more fierce and infrastructure will not handle it. We’ve also paved over the landscape, which has increased the amount that water flows. Adding parking lots and streets over time only makes it worse."

"But rain gardens can do everything to move it (water) slowly back into our water system. That’s a good way, but it will take lots of those all over the place. We’ll have to chip away at the bind we’ve gotten ourselves into. and bring some balance to the water system."

Conservative estimates argue Detroit has at least 24 square miles of vacant land.

Luckily, green infrastructure isn’t the most expensive solution. But they do require a lot of maintenance. Tending to vegetation and rooting out invasive species. The alternative would be spending hundreds of millions of dollars to overhaul the water systems of the region - money that Detroit and many other communities don’t have.

Larsen said the Great Lakes Water Authority - the region’s primary water regulator - is testing both solutions. But even that agency struggled through some of Metro Detroit's worst storms - particularly in June when some of its pumping stations were offline when heavy rain soaked the area.

"The thing is that for Detroit’s issues, the problems are not Detroit-specific. All rustbelt cities have these problems," she said. "But the vacant land is an opportunity. While the cost will be great, it’s something most cities don’t have."