Invasive hydrilla in Michigan a major threat to state's water bodies and economy

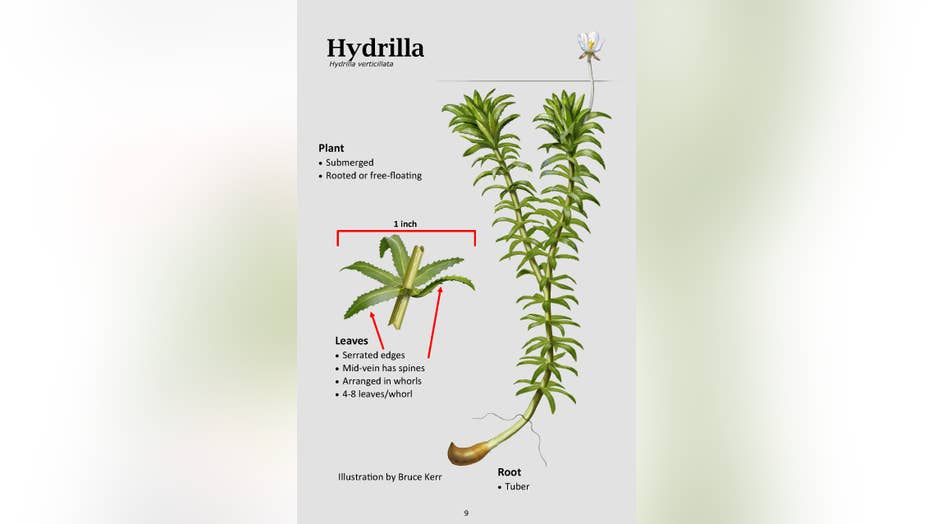

Hydrilla. Photo courtesy of Bugwood.org.

(FOX 2) - Bill Keiper remembers when he got the email. An attached photo showed the notable tubes associated with one of the most feared invasive plants in the country: hydrilla. It was bound to invade Michigan eventually. But its arrival is still a big problem.

"It's a disheartening moment for invasive species management. It's not what you want to find," he said.

Routine monitoring of two private ponds with no access to the outside world is what led to the detection. Officials were treating the water bodies for a different invasive species when they spotted the non-native monster.

When it got there and how it arrived is anyone's guess. But one thing is certain: its arrival is worrying.

"It takes six to eight years to control hydrilla. That's why we're so nervous about this plant," said Keiper.

Keiper's job in the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy is monitoring for invasive plants like hydrilla, then activating management protocols to contain the infestation. With hydrilla, his task has gotten much tougher.

Sometimes called "one of the most invasive aquatic plant species in the world," hydrilla can spread quickly with ease, requires little resources to grow, and can spawn in most water bodies.

And once established, the aggressive plant spells certain doom for the native species in the rivers and lakes it lives in. Already, it's become a major problem in the states it lives in, causing environmental, economic, and ecological damage in most of the eastern U.S.

It can kill water habitats and interfere with fish populations. The dense mats it creates can disrupt recreation and create major headaches for those that live and enjoy life on the water.

Until 2023, Michigan had avoided the challenges that come with managing hydrilla.

Then, last September in Southwest Michigan, two small populations of the species were found in private ponds on residential properties. Southwest by Southwest Corner Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA) was treating the area for a different invasive plant called parrot feather when they noticed the suspect plant.

"It's an odd circumstance. We thought it would show up in an inland lake or a river system. Instead, they show up in two landscaping ponds," said Keiper.

MORE: Invasive algae 'rock snot' found in Michigan stream used for fishing trout

Non-native plants typically arrive in new environments by hitchhiking with people or their boats and vehicles. Keiper's best guess for how hydrilla arrived is that it came through some other pond plants that had been planted there years ago, but struggled to spread due to the native algae that was already thriving.

Even with the disheartening news, Keiper considers the state fortunate.

"In reality, it could be way worse. At least it's in a small pond, that doesn't have huge public access," he said. "It's a very contained system."

How does hydrilla spread?

What makes hydrilla so feared is all the ways it can spread.

It can use specialized buds called turions that can remain dormant for years underground by turning into a plant. It can fragment itself and spawn from there. Its main mechanism is using specialized roots called tubers that overwinter in the bottom of ponds, rivers, and lakes, then spawn from there.

Hydrilla can also spread without much light while soaking up nutrients in the water, out-competing native plants.

And without a natural predator to keep its growth rate in check, its spread is almost guaranteed.

How do you treat hydrilla?

Because hydrilla can remain dormant for years without growing, managing a population requires years of continued monitoring.

One method is using herbicides - which isn't an option until after its tubers reveal themselves. The goal is to hit the plant as soon as it sprouts with a low concentration of fluridone that can suppress its spread.

In the ponds with the confirmed population in Berrien County, managers deployed the herbicide last year and again early this year. But due to the threat hydrilla poses, Keiper says they're planning to dredge the entire water body in hopes of eradicating the species.

"The risk of it hitting our inland lakes would become a huge burden for residents," he said.

With any hope, the detected population is the only one present in Michigan. Removing it would be a lot of work for one season, instead of continued risky monitoring for a decade; a short-term investment for long-term gain, says Keiper.

"Just because we treat this year, it could sprout again next year. But if we can dredge, we can remove the entire thing," he said.

Public asked to help

Like most invasive monitoring, the state always encourages the public to be vigilant. That way, a problematic species can be found sooner and make managing it that much easier.

For anyone with a water body on their property or spends time on rivers or lakes, they're asked to keep an eye out fort "something out of place that wasn't there before."

The plant isn't the easiest to identify, but it does have key characteristics beyond just being really aggressive. The tell-tale sign of hydrilla is its leaves. They grow in whirls of five along hydrilla's stalk.

If someone thinks they have found the plant - or isn't sure and is looking for an expert opinion - Keiper asks they take a photo and submit it to the state's invasive species monitoring network.

The Midwest Invasive Species Information Network (MISIN) can be found here. To notify the group, you'll need to create an account, then select "report" on the website. After that, select the suspected species.

The public can also send an email to egle-wrd-aip@michigan.gov with an image of the species and where they spotted it.