Minimum wage workers have to work almost 80 hours a week to afford 2-bedroom rent in Michigan

DETROIT - This is part one of our three-part series analyzing systemic housing issues for Detroit’s low-wage earners.

Despite the uncertainty of where she would sleep or what she would eat every night, there was one thing Jemica refused to ignore - personal hygiene. Sometimes she slept at her aunt’s place or her at her brothers, but she refused to come to school unclean.

“I ain’t coming to school smelly.”

But that was about it for normality when she was in high school. After she and her mom were kicked out of their apartment, she spent part of the summer living with her brother. But when summer vacation ended, she divided her time between living with her aunt and at different friend’s places - homes that were closer to school.

For Jemica, school became a place of respite; an escape from the struggles that awaited her after the bell rang.

“I used to love going to school because when I’m in school, I can just get away from all my problems and I just gotta deal with what’s going on in school and my work,” she said. “I just gotta deal with that.”

Despite difficulties that emerged in her senior year, Jemica proved to be a bright student in 9th grade. Her teachers saw fit to enroll her in honor courses the year after. Sure, geometry and environmental science weren't the easiest subjects to grasp, but school meant escape.

That escape was only temporary and Jemica would discover any chance she might have at a normal teenage life would be robbed from her due to an unstable life at home. Instead of relishing years meant for socializing and diving into new interests, she was forced to mature overnight.

“I never got to experience the normal teenage life. So like going to parties and stuff, I never went to a party in my life,” she said. “Birthday parties? Yeah. High school parties? Never.”

Jemica isn’t the only person who asks herself if she’ll have food waiting for her when she comes home. For Detroit’s poorest, food often comes second to the mandatory costs like housing.

In Matt Desmond’s 2016 book Evicted - which followed families in urban America’s poorest areas at the mercy of an impossible housing system - he said “Rent eats first.” Where amenities like dinner, a full tank of gas or a new pair of shoes can be put off until a later date, rent must always be paid.

“It’s different than other goods because you can’t cut back elsewhere,” said Dan Emmanuel, a senior research analyst for the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “That has cascading impacts on other issues.”

It’s generally assumed that people should never pay more than 30 percent of their income on rent. When rent exceeds this threshold, it forces those making little money to allocate an unsustainable amount of their income toward this mandatory cost. That leaves fewer dollars for the week’s groceries or medicine.

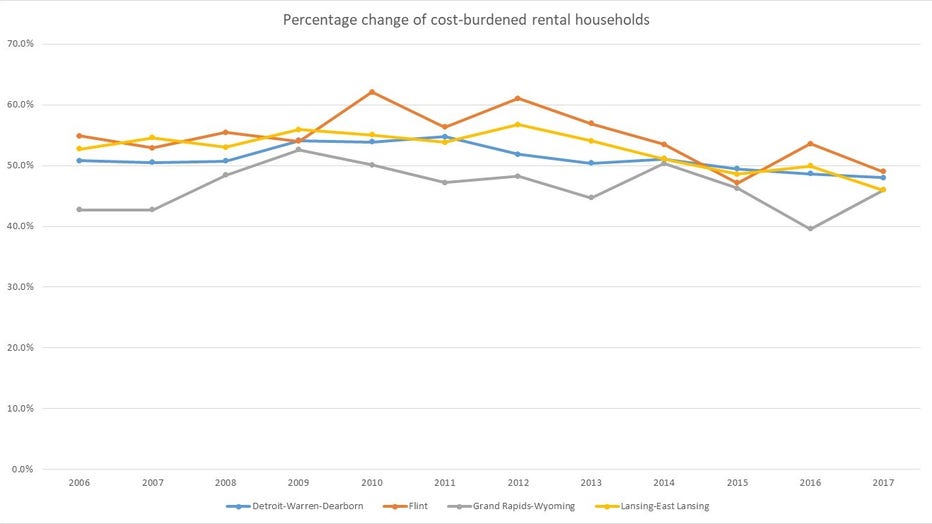

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies reported as of 2017, almost half of all renters in the Detroit-Warren-Dearborn metropolitan area spent more than 30 percent of their income on rent. The same study also found that, of those same renters, more than a quarter spent over half of their income on rent.

“It’s truly staggering to think about the number of people surviving on minimum wage,” said Luke Forrest, executive director of the Community Economic Development Association of Michigan. “In some cases, they work multiple jobs, some cases there are more people living together. Some people might be on social assistance programs.”

(Information courtesy of the National Low Income Housing Coalition)

You’ve probably heard public officials tout the country’s unemployment rate reaching historic lows. Since the unemployment rate eclipsed 10 percent after the recession in 2010, the country has seen continuous improvement in the job market. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports as of September 2019, the country’s jobless rate has bottomed out at 3.5 percent.

But that’s only half of the story. The wages that accompany those now-filled jobs have not kept up. Forrest said when adjusted for inflation, people make less now than the early 70’s. Workers making minimum wage in Detroit and Michigan have to work more than 40 hours a week if they want to afford average rent.

“These are good times in the economy, but wages haven’t grown,” said Forrest.

That’s not an estimation either. In their latest Out of Reach report, the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) reports for a person making minimum wage in the Detroit metro area, they have to work 58 hours a week to afford an average 1-bedroom apartment - either that or make 60 percent more money. The numbers are more grim for someone hoping to afford a 2-bedroom unit - they’ll have to work 73 hours a week.

Michigan's wage stagnation is not unique to the state. In fact, the OOR report ranked Michigan 29th on how much a resident will need to earn to afford an average rent in their state (for comparison, Hawaii ranked first at 111 hours a week at minimum wage to afford rent, while West Virginia ranked last at 54 hours a week).

What is unique to Michigan’s residents, however, is how old they are. Detroit is aging faster than most cities in the country.

While its population loss won’t be as stark after the 2020 census is completed compared to the 2010 census’s results, the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG) still estimates a continued population drop. Some of the biggest factors that explain this dynamic include a decline in birth rates among young people as well as a lack of immigration into the state. Those downward trends won’t replace an aging baby boomer population that will increasingly enter retirement.

Limited by mobility and a need for assisted living in cities, many seniors can’t afford to vacate their apartments, but can’t afford to pay for them either. While Michigan’s homeless population has been declining for years, 2018’s numbers are expected to show a leveling off of that trend. More concerning for the homeless action networks in Michigan and Detroit, seniors and families are increasingly making up the group of people with no place to live.

“The face of homelessness has really changed,” said Tasha Grey, executive director of the Homeless Action Network of Detroit (HAND). “It’s hit a population that people don’t usually think of.”

Grey said when they talk to families who are now homeless, the underlying sentiment was they had been employed when something out of the ordinary happened. Maybe a medical situation arose or they didn’t have the savings to support or maintain their housing.

When officials think of someone who is homeless, it’s no longer just the single man on the street holding a sign. Many that make up this population are experiencing it for the first time and those people were often low wage workers. After homeless numbers peaked in 2013 at 113,000, they continued to fall through 2017. However, the Michigan Coalition Against Homelessness reports that number saw a slight uptick in 2018. Its executive director said the rise is tied to affordable housing.

“A significant proportion of people who are homeless are working,” said Eric Hufnagel. “But they can't sustain their housing even though they are working. Not enough hours or not a big enough salary.”

Another factor in those homelessness numbers is after someone loses a place to live, they’ll struggle even more climbing out of that situation. HAND works with between 30 and 40 agencies in the city to provide temporary housing for the homeless. But temporary housing offers only a Band-Aid on a systemic issue.

Grey said when permanent housing is provided, the outcomes can be promising. While there is a growing movement to offer permanent instead of temporary housing, it’s still rare. For any in search of a cheap place to live, they’ll soon discover there aren’t many out there. That available stock has declined over the years and it’s magnifying the problem.

Overview: “Affordable is not affordable:” What happens when your city costs too much to live in

Part One: Minimum wage workers have to work almost 80 hours a week to afford 2-bedroom rent in Michigan

Part Two: Affordable rent is disappearing in Michigan

Part Three: Detroit's work to stop the next housing crisis

Jack Nissen is a reporter with Fox 2 Detroit. You can contact him at (248) 552-5269 or at Jack.Nissen@foxtv.com