"Shorts or boxers?": Riding with Motor City Mitten Mission

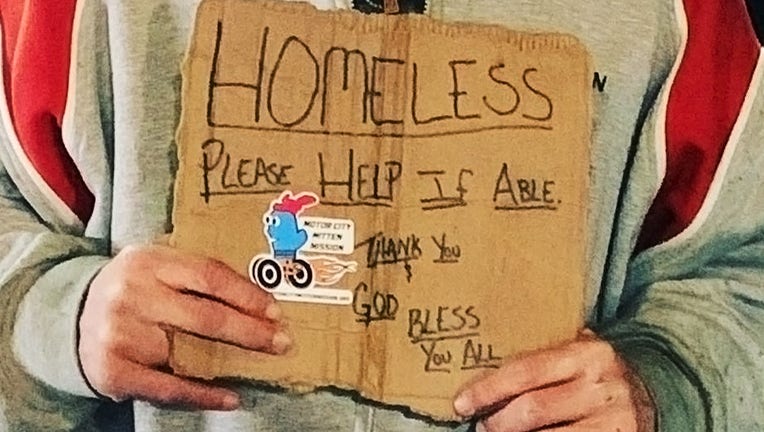

A man holds a panhandling sign with the Motor City Mitten Mission logo on it. (Photo courtesy of Motor City Mitten Mission)

DETROIT - Motor City Mitten Mission is a homeless advocacy group that delivers food, clothes, and other supplies to people around Metro Detroit, while also connecting them with housing and treatment options that fulfill urgent demands and satisfy long-term shelter needs.

For the last two months, we participated in several outreach sessions with Motor City Mitten Mission as they delivered supplies to clients that live in and around Detroit.

2:30 p.m. Sept. 5

Driving the Motor City Mitten Mission van takes nimble reflexes and keen observation skills during outreach. Serving the homeless means no corner or crevice of Detroit is too obscure not to seek when the goal is making contact.

On outreach sessions, volunteers stop at back alleys and abandoned buildings, under plazas, and in busy intersections. But today’s first stop isn’t for a client, but a volunteer.

Tom, one of Motor City Mitten Mission’s longest-serving volunteers, lives underneath an I-75 overpass.

When Rob, another volunteer goes to corral him, he opens the tent flap to reveal two feet pointing up. "Hey man! Good to see you!" Tom says, a big grin on his face.

Tom in his home near an I-75 overpass. Tom is one of Motor City Mitten Mission's longest-serving volunteers and helps out most days. (Photo courtesy of Motor City Mitten Mission)

Tom occupies a curious position in Motor City Mitten Mission - a housing services group that brings food and clothes to people around Metro Detroit. He works daily with the group but lives much like the people he helps. He's been offered a place to stay dozens of times but would prefer to live under a bridge. His skill as a carpenter is calculated and precise, but converse with him and he'll contort your brain with riddles.

"The thing about it is the thing about it," he once told Rob.

Tom prefers his tent - which rests on a platform he built himself that sits between two of the bridge’s beams - to sleeping in a home. It suits his secluded lifestyle. Inside his tent are clothes and flashlights that hang from the ceiling. Outside it is stacks of canned food, more clothes, and supplies next to a wooden cupboard he built himself. He also uses a miniature cooler to store food and a bike that hangs on the wall. The air is thick and the echoes of passing cars deafening. The real estate is smaller than a walk-in closet, but for hermits like Tom, it’s perfect.

Motor City Mitten Mission's first stop is here because Tom is part of Sunday's outreach team. Gail Marlow, the group's executive director, will drive while Rob sits a row back, ready to pass out supplies. For the next four hours, she'll navigate a maze of side streets and alleyways, stopping at street corners and boarded-up homes. The path isn't written down. It doesn't need to be. It lives in Gail's head.

That doesn't mean tiny modifications won't alter the daily route. A housing services group on the ground like Motor City Mitten Mission needs to be as adaptive as the population it serves is transient. But people that live on Detroit's streets rely on these three-person teams to feed and clothe them. Often familiar faces are in the same place, waiting for food, clothes, and hygiene kits.

That's where Rob comes in. As Gail drives, he'll be acting as a human swivel around the myriad supplies surrounding him that are packed into the van. At every stop she makes, he'll bag food and Faygo pop cans. It's likely each person they visit will be hungry. But sometimes they need a blanket or clothes. Motor City Mitten Mission has them. Occasionally, it's a new pair of shoes. The van carries most sizes. More often than not, it's cigarettes - too expensive to buy without an income but a great way to build faith with a population that struggles to trust someone offering a hand.

"Shorts or boxers?" Rob asks after someone says they need underwear. "What size jeans?" he calls out from the back of the van when someone asks for pants. "Menthol or non?" "Are size 13 shoes okay?"

But the most important service that Rob, Gail, and Motor City Mitten Mission offer is a path to stable housing. Nobody's path is the same. Personal barriers from lifelong mental health problems to severe drug addiction often exasperate a gap that little affordable housing and joblessness have already widened over years - or decades.

7:30 p.m. Sept. 15

"He's sick Gail. He's really sick."

The Motor City Mitten Mission van is parked in the loading dock area underneath Hart Plaza in downtown Detroit. Gail is again the driver, but this time it's Cody that's running point on supplies distribution.

No stranger to homelessness, Cody was searching along the Detroit River banks when he found someone sleeping next to the Detroit Princess Riverboat. After bringing him back to the van, he swings the door open and starts digging through duffel bags. His voice is frantic.

"He's competent enough to answer questions, but he'll go off on a tangent. You can tell he's hearing voices."

In the loading bay underneath Hart Plaza in downtown Detroit. Gail, Norris, and Cody talk with a man who was staying near the Detroit Princess Riverboat. (Photo via Jack Nissen)

Norris Howard, a behavioral specialist that is along for the day's drive, agrees. The man, later identified as Mark is shirtless, has intense body odor, and is delusional. "His family apparently owns jewelry stores all around the world," Howard says.

He's not a danger to himself or anyone else, Norris determines after a mental health evaluation. Along with food and water, the Motor City Mitten Mission gives him a sleeping bag, clothes, and most importantly, Gail's phone number. They ask if he'll be there the next day so they can stop by with more food tomorrow.

Norris assists Motor City Mitten Mission during the organization’s Detroit pilot days - outreach sessions where volunteers focus on the city’s 3rd precinct and downtown. That's where police get the most calls about someone in the middle of a mental health episode or creating disturbances around other people. Gail gets calls from people all over the city, but organizers of the pilot project want her to focus on those areas.

Hours earlier, Motor City Mitten Mission started its outreach at the Eight Mile Road overpass over I-75 where homeless people like to congregate. Along with the Woodward Avenue overpass, it's a popular place to panhandle.

One of Motor City Mitten Mission's cell phones had gotten calls from a man named Brian. He's been desperate the last four days - he needs help. After parking, Cody calls Brian and tells him to meet them there. As they wait, other people begin showing up. That includes Calvin, who is wearing a hat that reads "Leslie Knope for President."

Soon enough, Brian shows up. His clothes are torn and he has an unkempt face. There are bags under his eyes. He's been sleeping in an unlocked truck at a nearby mechanic shop. He had been living with his mom before she died. Then his landlord kicked him out.

In a moment of quick thinking, Gail decides to perform a background assessment of Brian. It usually happens at the office, but Brian is newly homeless and wants to be off the streets now. Chronically homeless people can take years to convince to seek help, but those recently stricken by a loss of housing might be ready for help immediately. She asks him dozens of questions about himself, scrutinizing his criminal past, mental health, drug addiction, and interest in a job.

"I'm not a greedy person. I'll work. I just want a place to stay," he says.

At this point, Cody has passed out meals to four more people. He knows most of them - or at least knows their names. Identifying someone by their name goes a long way in this line of work.

Brian qualifies for housing. That's the good news, Gail tells him. But he may need to wait weeks before a spot opens up. It'll be the first step on a long road to more permanent housing. For now, he'll need to stay on the streets. But Gail and Cody promise to keep in touch.

About 15 minutes later after the van arrives at Central City in Detroit, Norris is the next person to climb inside. The partnership between Motor City Mitten Mission and Detroit includes a behavioral specialist who can expedite mental health services to help people struggling.

"What's your name?" asks Norris, after someone walks up to the side of the van.

"My name's Mike Early. I'm Mike Early because I'm never late!" the man replies.

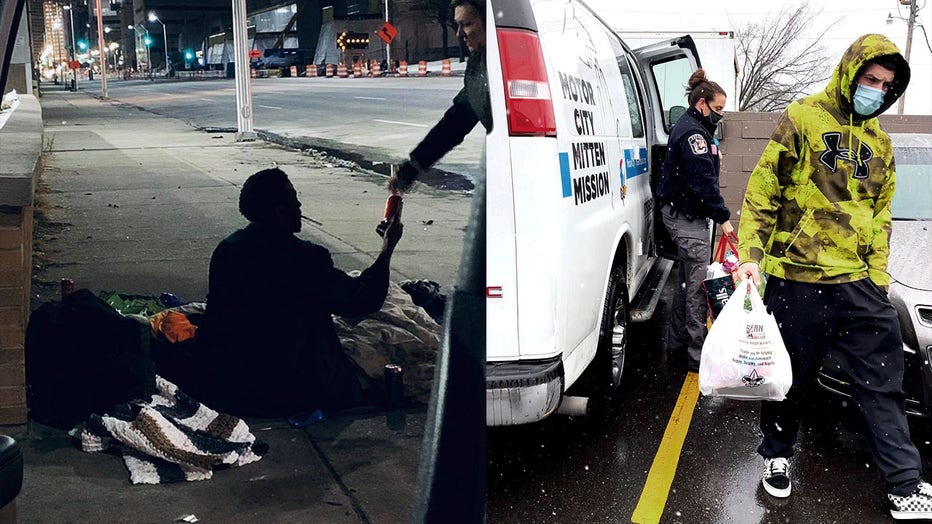

(Right) A volunteer hands a pop to a man staying on the street. (Left) Cody exits the Motor City Mitten Mission outreach van with supplies. (Photo courtesy of Motor City Mitten Mission)

Normal interactions during Motor City Mitten Mission outreach sessions start with the van pulling up to where someone is. But the organization has a growing reputation in Detroit as a homeless service that comes to its clients. They make trips every day. People have become familiar with the mission's logo: a face overlaid on a blue mitten with wheels and a flame behind it. If it's not the organization's emblem that people recognize, it's the person driving the van.

The next stop is another man named Mike, whose panhandling on the corner of Cass over I-75. Rob spoke with him a week before, Cody says, but in the weeks since no one from the mission has seen him. "I'm from out of town," Mike tells Gail.

His emergency contact is his brother, but he has no ID or wallet - not unusual with homeless people, but it can make getting housed difficult. "That's okay hun, we can get you a temporary ID from HUD," says Gail.

After Cody gives him clothes, shoes, food, and a promise of returning, the van is on its way.

5 p.m., Sept. 30

Rob is pulling up to an abandoned home on the city's southwest side and honks the horn. Jeremiah is in the passenger seat - he's a new volunteer who is recently housed. If someone comes out, they'll hand them food. If no one comes out they'll leave food all the same.

This time, someone does. It's Rico, who hops a fence. A dog is behind him, but can only watch from between broken planks within the fence.

"Hey man, how are you doing?" Rob asks. "Think you're ready to get housed?"

"I'm like 30% there, man," he replies. That's progress from where he used to be.

Inside the Motor City Mitten Mission outreach van. While out on assignment, volunteers will pass out food, clothes, drinks, blankets, and hygiene kits that are stored inside. (Photo courtesy of Motor City Mitten Mission)

Homeless people often inhabit a squishy malleable area of life's in-between - fed up with living off of society's scraps, but not ready to return to its regiment. For people like Rico, who have people checking up on them every day, a friendly face offering assistance can be enough to convince them to take the help.

But Motor City Mitten Mission's clients don't always live on the spectrum of "ready or not." Severe mental illness and rampant addictions rankle many of them. And the formula needed to convince them to seek help requires persistence.

It took persistence to convince Jeremiah. He was one of the two holdouts at Hart Plaza in May 2021 after police cleared the encampment that was there. He was offered a place to live, food, or cash. Anything, if he would just move.

But he didn't. Motor City Mitten Mission had been making daily visits and noticed he had deteriorated. He was rambling about having kids in California and that aliens were coming for him.

Then he disappeared. Motor City Mitten Mission visited Hart Plaza every day while he was missing, serving the remaining client that was staying there. Two weeks later, Jeremiah reappeared, wearing the same clothes he had when he left but with a different demeanor. He was noticeably friendlier and cognizant.

Jeremiah had checked himself into a hospital, volunteers later learned. He got an injection that gradually medicated him over time. When they saw him again, Motor City Mitten Mission offered help that he took. They offered to get him housed, which he also capitalized on. Now he goes out on outreach every day he can.

It’s not uncommon for clients to become volunteers. Most of Gail’s staff is made up of formerly homeless people. It makes for a dysfunctional business model as schedules constantly change or workers disappear. Some still struggle with addiction and will relapse. Others aren’t ready for the responsibilities of regular work.

Before he started helping Gail, Cody counted himself as those that weren’t ready. "When you’re a homeless addict or even homeless period depending on how you look at it, it becomes a lifestyle," he said one night.

"When people find a way to live on the streets and satisfy whatever needs you want to personally satisfy, whether it be fueling a drug addiction or just being left alone, there's a whole bunch of components that go into it."

Cody had just gotten out of jail when he joined Motor City Mitten Mission. He says his last year of living on the street was hell. He had been shot, almost lost his leg twice, and nearly died on multiple occasions. In addition to drug addiction, he was underweight.

That’s a lot of baggage to bring into a job. But those experiences offer valuable insight into the mind of someone still on the streets. Workers can empathize with their clients and speak from a familiar place. Common ground is vital to this line of work, Gail says, because it helps contextualize an issue that is often misunderstood.

"It’s hard to say to somebody ‘let’s get you employment,’ when somebody has a heroin or alcohol habit they have to feed within the next few hours," said Gail.

8:30 p.m., Sept. 30

The last stop of the day is at a motel off of Jefferson Avenue near downtown. Despite servicing some 70 people today, Motor City Mitten Mission needs to ration a couple dozen meals and drinks for this final stop. With a duffel bag of food, Faygo cans, and water, Rob will sweep through both floors of the motel and knock on specific rooms.

One person who comes to the door is Frank, who used to live at Hart Plaza with Jeremiah. Both now live here. He was staying at the Rivertown Inn before getting kicked out. Confusion between housing groups assigned to him caused the mistake. Now he’s at the motel. He’s always happy to see the volunteers.

At another door are two kids. Two more can be seen inside the room. They’re one of several families staying at the motel.

Gail hands supplies to a family staying at a motel. (Photo courtesy of Danny Wilcox Frazier)

The motel is one of Motor City Mitten Mission’s greatest assets - giving dozens of people as young as elementary kids and as old as seniors a place to live. It makes servicing clients easier since they all stay in the same place. Here, people can find some consistency after years of sleeping in shelters or on the streets. And once their voucher is pulled, they’ll be ready to move into a housing unit where they’ll pay subsidized rent as they work back into society.

But the growth of motels and hotels as a temporary housing solution also paints a more complicated picture of what homelessness looks like. It’s not just a single individual sleeping on the street. It’s seniors on a fixed income who can’t afford to live somewhere more stable. It’s families with single parents struggling to feed their kids and pay rent at the same time.

It’s one of the reasons rent and hotel costs are one of Motor City Mitten Mission’s highest expenses, Gail says. It likely will be again the next time she meets with her board. Their board president, Susan Wood, has been with Gail since she started the organization.

Back in 2018, Motor City Mitten Mission had a budget of $15,000 and one volunteer - Gail, who lived off her savings as she built the organization. Now she has dreams of expanding the motel component into something bigger.

Susan says Gail’s networking and exhaustive work ethic have enabled the group’s success and growth. But it also requires a bit of innovative thinking to re-imagine how to reduce homelessness.

"I’m not sure how many groups are doing this," Susan said. "It’s very costly because you’re reaching smaller numbers of people, rather than having them come to you.

"This was Gail’s way of initially making contact with so many people that have fallen through the cracks. When I see the relationships that Gail has with some of these people, when I see that report and trust that clients have, it’s only because of her consistently going out."

The group’s budget has ballooned to $500,000 this year, rising on an almost logarithmic scale. Donations from the board, awarded grants, and charity drives have helped feed the group’s momentum on the streets. It still doesn’t feel like enough, Gail says.

Gail inside the Motor CIty Mitten Mission van. Once the most frequent faces during outreach, clients often ask "Where's Gail" if she's not driving. (Photo courtesy of Motor City Mitten Mission)

The money goes toward food, supplies, drinks, clothes, and sleeping bags for people on the streets. It also pays for their living expenses as they wait for help for urgent health problems. If they want, they’re welcome to assist at the organization’s headquarters where they’ll make some extra cash.

When clients turn for help, Gail sees that as an improvement. If they want to help themselves, that’s more progress; both for them and her methods for approaching homelessness. Her success was on display earlier in September during the Detroit Lions opening game.

Gail was in the stands that game with about 20 other people. Some were volunteers and others were clients: Jeremiah, Rob, Cody, Orlando, to count a few.

"A few months ago, some of those guys weren’t even in the right headspace. I couldn’t imagine them interacting with someone, let alone going to a big event like that.

"So yeah, I think it’s working."

Learn more about Motor City Mitten Mission at their website here.

Jack Nissen is a reporter at FOX 2 Detroit. You can contact him at Jack.Nissen@fox.com or at (947) 517-2294