The great algae problem on Lake Erie - caused by fertilizer, solved by time and effort

FOX 2 - On the western edge of Lake Erie is a green, oily sludge that comes out regularly every summer and lasts into the first month of fall. It's a green algae bloom and it's not going anywhere.

Dr. Timothy Davis is a professor of biological sciences at Bowling Green State in Ohio and says this problem is not one that the Buckey State must solve alone or that is strictly only a problem for Lake Erie. This problem is much better than any of us.

Algae blooms on Lake Erie cause serious problems

Derek Kevra takes a closer look at the algae bloom issue on Lake Erie and the potential effects including a threat to our drinking water.

If you've ever been on the Michigan side of Lake Erie in the summer, you've probably seen the green sludge that takes over the west edge of the lake. The bad news is this isn't going anywhere and it's not just an Ohio problem or a Lake Erie problem.

"This isn't just an Ohio problem or a western Lake Erie problem, this is a Great Lakes problem and, frankly, a global problem," Dr.Davis said.

The problem is this: every year, beginning in July and continuing until sometimes October, the western side of the lake explodes into this green sludgy mess. It's kind of slimy and almost looks like green paint on top of the water.

The layer on the surface is called cyanobacteria and forms due to nutrients from fertilizer that get into the water.

"These excess nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorus, is what is fueling these blooms," Dr.Davis said.

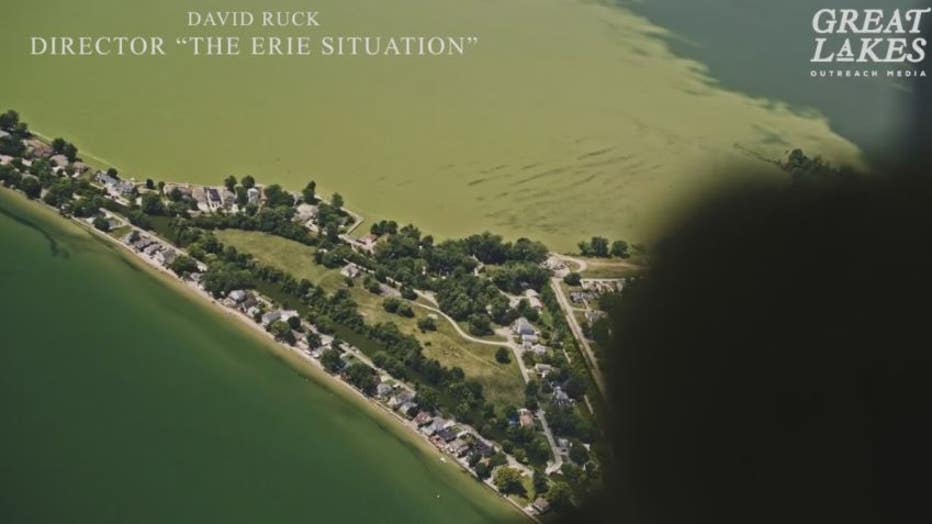

The blooms are routinely 300 square miles and can be seen from satellites in outer space. Footage shot by filmmaker David Ruck for the upcoming film "The Erie Situation" from Great Lakes Outreach Media shows a small part of a very big problem.

"We get blooms that can be up to 5 or 6 times the size of Washington, D.C.," Dr. Davis said.

The algae blooms have been around for decades but they got significantly better in the 1970s and 1980s thanks to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Then they came back and are different from the ones we experienced 50 years ago.

"We kinda took our eye off the ball and they essentially resurged," Dr. Davis said. "The blooms we see today are different than the ones we saw in the 60s and 70s because they seem to be much more toxic and they're dominated by a different organism than the blooms were back then."

That toxicity is putting people like Mike Briskey, who is the general manager of Luna Pier Harbour Club & Marina, at risk. He says during a bad bloom, his family's 35-year-old marina and bait business plummets as people don't get on the water and the fish don't bite.

"For the smaller boaters that don't wanna go that far offshore their choice may be to stay home or go play golf or do something else. They're not shopping with me no," said Briskey. "The number of limit catches is down. The numbers of people that go out and have a completely unsuccessful, that's up."

The bloom led to the 72-hour Toledo Water Crisis in 2014 when the wind blew the algae right toward the water intake valve.

"All of a sudden the intake was taking in water with a lot of toxin in it...into the finished drinking water which then leads to the do not drink order to be issued," Dr. Davis said.

The algae problem has been getting significantly worse since 2002 and climate change is likely to blame.

"We've seen two of the largest blooms in recorded history in the last 10 years." Dr. Davis said. "Warmer temperatures can produce blooms that are more intense and possibly even more toxic."

The reasons are two-fold, according to Reagan Errera, a NOAA Great Lakes Environment Research Laboratory ecologist.

"We're getting warmer and our water temperatures are getting warmer and cyanobacteria like it hot," she said. "They like warmer water so when it's warmer, they'll do better."

A changing climate means a changing rain pattern, which is an even larger issue.

"We have changing precipitation patterns too, so we have more rain. More rain means more runoff, more runoff means more nutrients, more nutrients means larger blooms," Davis said.

To combat this, it's going to take a team effort and it may start with farmers like Jason Ruhlig. He's using GPS technology to become more efficient at spreading fertilizer.

"We're making sure we're only putting a minimal amount of fertilizer on, in the areas where it's needed and not where it's not needed," Ruhlig said

He also says farmers are utilizing more cover crops to soak up the old nutrients

"You can see behind me, the brown, that was oats that we planted last fall so those nutrients that were leftover from the soil we plant those oats," he said. "They pick up all those nutrients and they store them in the plant material."

To solve the problem, it will really take a team effort and time.

"It's a difficult task - it's not impossible. We have evidence that we can do it. We've done it once in Lake Erie already, but it takes time and patience. There's no quick fix for Lake Erie" Davis said.