Fact checking claims from the 2020 Democratic debate in Detroit

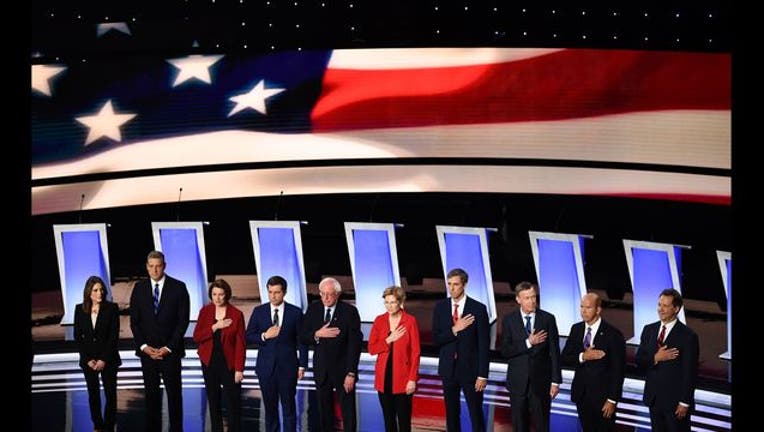

Democratic presidential hopefuls during the national anthem ahead of the first round of the second Democratic primary debate in Detroit. (Photo by Brendan Smialowski / AFP) (Photo credit should read BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty Images)

WASHINGTON (AP) - Ten Democratic presidential contenders vied for advantage Tuesday night in the second round of the party's 2020 campaign debates.

A look at some of their statements in Detroit and how they compare with the facts.

BETO O'ROURKE, former U.S. representative from Texas, on global warming: "I listen to scientists on this and they're very clear: We don't have more than 10 years to get this right. And we won't meet that challenge with half-steps, half-measures or only half the country."

THE FACTS: Scientists don't agree on an approximate time frame, let alone an exact number of years, for how much time we have left to stave off the deadliest extremes of climate change.

A report by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, drawn from the work of hundreds of scientists, uses 2030 as a prominent benchmark because signatories to the Paris climate change agreement have pledged emission cuts by then. But it's not a last-chance, hard deadline for action, as it has been interpreted in some quarters.

The report forecasts that global warming is likely to increase by 0.5 degrees Celsius or 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit between 2030 and 2052 "if it continues to increase at the current rate." The climate has already warmed by 1 degree C or 1.8 degrees F since the pre-Industrial Age.

As much as climate scientists see the necessity for broad and immediate action to address global warming, they do not agree on an imminent point of no return.

___

BERNIE SANDERS: Benefits under his health care plan "will be better because 'Medicare for All' is comprehensive and covers all health care needs."

THE FACTS: On paper, the Vermont senator is right. In real life, if he's elected president, the result might be quite different.

Sanders' "Medicare for All" bill calls for a government plan that would cover all medical care, prescriptions, dental and vision care, mental health and substance abuse treatment, and home and community-based long-term care services with virtually no copays or deductibles. The only exception would be a modest copay for certain high-cost medications.

But other countries with national health care plans are not as generous with benefits and also make use of copays to manage costs. Canada, often held up as a model by Sanders, does not have universal coverage for prescription drugs. Canadians rely on a mix of private insurance and public plans to pay for their prescriptions.

If Sanders is elected president, a Congress grappling with how to pass his plan may well pare back some of its promises. So there's no guarantee that benefits "will be better" for everybody, particularly people who now have the most generous health insurance.

___

SANDERS: "49 percent of all new income is going to the top 1 percent."

THE FACTS: That is probably exaggerated. The figure comes from a short paper by Emmanuel Saez, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, and leading researcher on inequality, and doesn't include the value of fringe benefits, such as health insurance, or the effects of taxes and government benefit programs such as Social Security.

But Saez and another Berkeley economist, Gabriel Zucman , have recently compiled a broader data set that does include those items and finds the top 1% has captured roughly 25% of the income growth since the recession ended. That's certainly a lot lower but still a substantial share. Income inequality has sharply increased in the past four decades, but since the recession, data from the Congressional Budget Office shows that it has actually narrowed slightly.

___

TIM RYAN, U.S. representative from Ohio: "The economic system that used to create 30, 40, 50 dollar-an-hour jobs that you could have a good solid middle class living now forces us to have two or three jobs just to get by."

THE FACTS: Most Americans, by far, only work one job, and the numbers who juggle more than one have declined over a quarter century.

In the mid-1990s, the percentage of workers holding multiple jobs peaked at 6.5%. The rate dropped significantly, even during the Great Recession, and has been hovering for a nearly a decade at about 5% or a little lower. In the latest monthly figures, from June, 5.2% of workers were holding more than one job.

Hispanic and Asian workers are consistently less likely than white and black workers to be holding multiple jobs. Women are more likely to be doing so than men.