Invasive hydrilla in Southwest Michigan ponds required massive removal effort

Hydrilla plants can be seen along the surface of the water at Selden Cove in Lyme, a cove that is part of the Connecticut River on Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2023. (Aaron Flaum/Hartford Courant/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

(FOX 2) - It took a lethal herbicide, digging up entire bodies of water, hundreds of thousands of dollars, and years of planned monitoring for Michigan environmental officials to rid an invasive plant species from two properties.

Ridding hydrilla from its only known location in Michigan required a monumental effort. And yet, officials fully expect it to return to the state - and in greater force.

Big picture view:

Dubbed the "world's most invasive aquatic plant," hydrilla is almost impossible to remove once it's established in a water body. That reality was cemented by invasive species experts who learned it was growing in two private ponds in Southwest Michigan in 2023.

The state's response was extreme - and it needed to be, according to Billy Keiper, an invasive aquatic species monitor with EGLE.

"This is the highest risk species" on Michigan's aquatic plant watch list, Keiper said during a recent webinar.

Because of the plant's ability to spread - either with tubers or seeds or fragments that fall off its main stem - and its ability to withstand repeated removal efforts, monitors opted to blast the two Southwest Michigan ponds with an aggressive herbicide in early 2023.

A full-season dose of fluridone killed everything in the ponds.

Unfortunately, hydrilla tubers survived, leading Keiper and EGLE to literally remove the ponds.

The backstory:

The ponds where hydrilla was discovered are connected to a creek that flows into the St. Joseph River.

Had the plant made it to the Southwest Michigan channel, it would have a direct connection to Lake Michigan. Because eradicating an invasive species is only feasible if it hasn't spread, keeping it out of the St. Joseph River was essential to keeping it from establishing in Michigan.

Except for Antarctica, hydrilla has spread to every continent on Earth. First discovered in Florida in the 50s, it has creeped up the eastern U.S. seaboard, planting roots in dozens of states.

Officials believe it found its way into Michigan as a hitchhiker, likely along some ornamental nonative pink waterlillies that were also in the ponds.

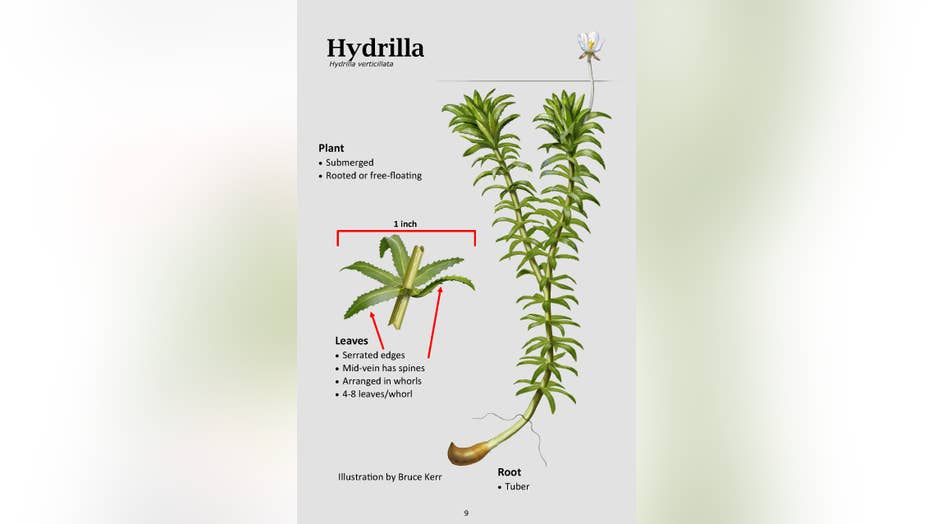

While it looks similar to other native plants like elodea, it has some distinct features, including a whorl of five leaves with serrated edges. It has sprouts white flowers that appear above the water's surface and can grow up to 30 feet in length.

"We don't know how long its been there, and that's the best guess we have," Keiper said of the local infestation.

Dig deeper:

In 2024, a large partnership opted for "mechanical removal" of the two ponds. In other words, it didn't hold back.

The water was drained into nearby wetlands. After that, the sediment would be dug up by excavators and placed into disposal tombs and eventually buried on site.

While pond one was dredged without a problem, pond two didn't go as planned. Officials found a notoriously toxic metal called arsenic, requiring an entirely different removal method. Officials were forced to truck the soil to a landfill instead.

Meanwhile, another pond nearby kept flushing water back into the targeted ponds as winter and spring temperature swings made conditions muddy and tricky to manage.

The whole process took several months and cost $239,000 to rehabilitate.

It will require several more years of monitoring to ensure the plant doesn't come back.

The ponds where Hydrilla was discovered in Southwest Michigan.

Zoom Out:

By mid-June, the newly built ponds had sprung back to life.

While no hydrilla had emerged, the first pond did spring back to life with native charo filling in the water - an indication that even after all the landscaping, nature will find success.

"I'm not sure if that's good or bad," Keiper said. "The verdict is still out on that."

Keiper said the chance that any hydrilla fragments surviving EGLE's scorched earth plan is pretty low. But he's not ruling out it could be waiting to appear.

"I'm cautiously optimistic that what we did was successful," he said, before adding an ominous warning.

Last year, invasive species monitors on the lookout for hydrilla detected the plant in Illinois and Ontario, nearing the borders of Michigan and increasing the likelihood it will one day be back in the state.

"It's still coming," he said.

The Source: An invasive species webinar from the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy and previous reporting was used for this story.